Breadcrumbs navigation

Unlearning as pedagogical practice: relational, embodied and place-based shifts

Claire Timperley and Kate Schick were joint winners of the 2022 Award for Distinguished Excellence in Teaching International Studies. Claire and Kate have sought to contextualise their teaching of International Relations and Political Theory in relation to the land on which they teach, making relational, embodied and place-based shifts to their pedagogical practice. In doing so, they seek to acknowledge their roles as settler educators on Indigenous land.

As settler educators living on Indigenous land, we seek to recognise and reflect on the privileges that have enabled our education and careers. This critical reflection has raised difficult questions about our presence in an academy that is, by-and-large (though not always), supportive of people who look and think like us, and often hostile to those not raised in the Western tradition. Much of our work as educators in recent years has been focused on unlearning and dismantling some of the assumptions that have been deeply embedded in our thinking and practices as scholars and educators. The aim of this short blog post is not to decode or explore all the tensions we experience as we occupy fraught positions of power, but to share some of the practical steps we have taken in order to address some of the systemic injustices we see in the academy, especially in the context of learning and teaching.

Learning As Embodied, Relational and Place-Based

We are committed to pedagogical practices and research that are embodied, relational and place-based. Over our teaching careers, we have developed praxis that centres students and their experiences, resulting in more holistic teaching and assessment methods that recognise students as people, not just learners. As well as being emphatically student-led, we are continually deepening our understanding of living on Indigenous land and how that influences both the content and form of our teaching. We seek to incorporate Indigenous language and epistemologies in our classrooms, but are sensitive to issues of cultural appropriation. As non-Indigenous scholars, we explicitly talk about our presence in the classroom and the structural context that has enabled us to succeed. We also draw from non-hegemonic Western traditions that value relational and embodied learning, exploring the ways that these methods and forms support students from backgrounds that have traditionally been ‘othered’ in the academy, particularly Indigenous students.

Small interventions

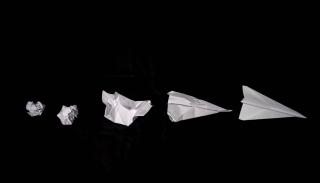

Recognising learning as relational and embodied means not only changing course content to better reflect diverse intellectual traditions, but also changing the format of our teaching and our assessment. Although we have made significant changes to our course design over the years, we have also experienced the power of small interventions in transforming students’ learning - simple and low-effort interventions can have outsized effects.

For example, we both get our students to spend a short time reflecting on their learning either at the beginning or end of the class. Kate chooses for students to use the first five minutes of class in silent reflective writing before they share their thoughts with their peers. Students find this practice immensely centering: it not only prepares them to learn and engage with their classmates, it also helps them to more deeply integrate their learning on a personal level. For students with learning differences or who need time to process internally before sharing, this practice can be transformative.

Claire asks students to spend five minutes at the end of class to reflect on what they’ve just learned, using a set of prompts encouraging them to consider what was new or surprising to them, what they wish they had engaged with more or still felt like they didn’t understand, and to think about the connections between the class and their everyday experiences. In some classes, she will share anonymised versions of these reflections with the relevant facilitator for them to draw on in their own self-reflection about their facilitation. This activity aims to create engagement between students, it gives them practice at giving and receiving constructive feedback, and it offers an opportunity to develop critical thinking and practices of patience and gratitude.

Larger interventions

Larger interventions include Kate’s design for relational learning environments via the use of ‘micro-communities of learning’. She pre-assigns students to groups of approximately eight at the beginning of the semester, and their learning throughout the course happens primarily in these groups. Students reflect, discuss, write, peer review, and present in their micro-communities and, over time, come to know and trust one another. Students report finding these diverse groupings a powerful site for learning, saying that their willingness to be vulnerable and to support one another in exploring new ideas leads to rich and deep learning that goes far beyond absorbing information from a lecture or text.

Claire has redesigned assessment in her courses to centre students-as-experts, offering options for creative project assignments that allow students to share their learning through varied media. Students can submit paintings, podcasts, Māori carvings, songs, board games, short stories, sculptures, embroidery - projects that are meaningful to them in relation to the course content - which they then narrate via a critical reflection, explaining what aspects of the course they engaged with, why they chose their particular medium to express themselves, what they learned about themselves and the thinkers they engaged with, and what they would do differently if given the option.

Ongoing (un)learning

We have sought to give you a glimpse into how our thinking as educators in Aotearoa New Zealand has developed over our careers, as well as some practical steps we have taken to address the difficult questions we face as educators living on Indigenous land. Ultimately, there are structural issues that need to be addressed to more fully respond to these questions, including addressing the serious under-representation of Indigenous scholars and educators in the academy (McAllister, Kidman, Rowley and Theodore, 2019). But we also believe in the importance of everyday actions in shaping our learning and teaching, and seek to intentionally reflect on ways we can support the liberatory aims of critical pedagogy.

Kate and Claire have co-edited a book, Subversive Pedagogies: Radical Possibility in the Academy, in which they further explore these ideas, alongside reflections from other scholar-activists in Aotearoa New Zealand and internationally.

Authors

Claire Timperley is Lecturer in Political Science at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand. Her teaching and research interests include feminist political theory, gender politics, critical pedagogy, and the politics of Aotearoa New Zealand.

Kate Schick is Senior Lecturer in International Relations at Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington. Her teaching and research interests lie at the intersection of critical theory and international ethics.

Photo by Joshua Dixon on Unsplash