Breadcrumbs navigation

Why studying the late twentieth century is crucial for understanding IR today

In 1977, three decades into the Cold War, Stanley Hoffmann termed International Relations (IR) “an American social science”. In the years following, world politics would transform markedly, not least with neoliberal globalisation and the fall of the Soviet empire. Did the discipline designed to study that world change with it? For Sam Dixon, a PhD student researching the history of IR in the late twentieth century, the answer is surely a (qualified) “yes”. He wonders why disciplinary historians have largely overlooked a period that explains so much of IR today.

In a famous 1977 essay, the Harvard professor Stanley Hoffmann described International Relations (IR) as “an American social science”. The United States, he argued, was the only country where IR had become a professional discipline with international reach – and for typically “American” reasons.

Of these reasons, the most important were the scientific reformism of US culture and society; the integration of exiled European scholars of realpolitik; and above all “the rise of the United States to world power” after 1945. Together these turned IR from a transatlantic field of enlightened foreign affairs discussion into a science, whose purpose was to uncover “laws” of state interaction to inform US policy during the Cold War. These laws – of ever-present power struggle and clashing national interests – were illuminated by the theory of “realism”. Yet this was parochial knowledge posing as universal, Hoffmann believed, ignoring historical change, international hierarchies, and their philosophical stakes in an age of transition.

Over forty years later, do Hoffmann’s arguments still apply? Today, despite the essay’s canonical status, its relevance is ambiguous. While it has often been a touchstone for stock-taking assessments of IR’s development, this has been as much to highlight changes as continuities. Meanwhile, it has been invoked by “mainstream” and “dissident” scholars alike to legitimise their centrality or marginality within IR, often to the neglect of Hoffmann’s original purposes. With détente and the crisis of the post-war international economy, times were changing in the 1970s, and world politics would soon transform further with the fall of the Soviet empire. Would the discipline designed to study that world change with it?

Still Hoffmann’s American Social Science?

Through an intellectual history of IR scholarship in late-twentieth-century Britain and the United States primarily, supported by available archival material and interviews and correspondence with scholars, my PhD seeks an answer to this question. One particularly interesting finding has been that no matter whether the discipline changed in the ways Hoffmann hoped, his essay was itself indicative of change.

In my research, I highlight an increasing disciplinary self-awareness from the 1970s, which was driven – in part – by the late arrival of IR to mid-century debates in social theory and philosophy of science. Yet, as I seek to show, this was entangled with a broader institutional expansion and intellectual diversification of IR amid global change, the extent of which was itself the subject of fraught self-examination. In an era of blurring boundaries between domestic and international affairs, the rise of human rights, a globalised knowledge economy, and international power shifts, IR was forced to reflect on itself and its relation to a changing world.

Accordingly, it was in the late twentieth century that I argue “IR” – the swish acronym popularised in this period – became recognisably what it is today, with a cachet and consciousness of its identity as a social scientific discipline, and growing institutional and intellectual profile in a globalising world. Though the US discipline remained central while itself evolving, these changes were boundary-crossing processes that saw other national and transnational communities consolidate, including – notably – in Britain. Ironically, this occurred just as international politics was supposedly losing distinctiveness, and IR catching up with other social sciences. Just as curiously, these changes have largely escaped the attention of those who began writing the history of IR in this period.

Forward to the Millennium: The Third Debate(s)

Hoffmann’s was not the only sociological account of IR promoted in the late twentieth century. Soon, another narrative took hold that IR was evolving. This was the infamous “Great Debates” story, in which IR was said to have progressed through phases of paradigm dominance in the twentieth century. While the world wars and behavioural revolution set the scene for the First and Second Great Debates between idealism and realism in the 1930s, and classical and scientific methods in the 1960s, realism (in “neorealist” scientific form) was now itself challenged.

While it is often assumed the Great Debates myth was purely invented by realists to establish their scientific credentials, it was cemented by the reception of Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962) during IR’s “Third Debate”. What IR commentators took from Kuhn was the idea of incommensurable paradigms – taken-for-granted thought structures which oriented progressive research in scientific disciplines. It was believed Kuhn helped comprehend not only IR’s evolution, but also define a new “dividing discipline”, where scholars approached an increasingly complex world from conflicting – if equally important – angles.

There were two overlapping interpretations of the Third Debate. The first, reflecting IR’s turn towards economics during the 1970s, described an “inter-paradigm debate” between realism, liberalism, and Marxism. This was a contest over declining US power and the autonomy of the state after détente and the demise of the Bretton Woods system, an ideological clash between visions of world order “after hegemony”. The second and broader interpretation, popularised at the Cold War’s close, noted increasing divergence between positivist approaches – which premised IR on natural science – and self-described “dissidents” who rejected them. Exploiting intellectual space opened by liberals and Marxists, dissidents drew on critical social theorists such as Jürgen Habermas and Michel Foucault to comprehend a now even more rapidly changing world.

An eclectic group including everyone from constructivists to postmodern feminists, critical scholars were united by a belief in the inseparability of knowledge and reality. Contrary to the value-free “laws” of neorealism especially – which they often saw, like Hoffmann, as an ideology of Cold War containment – critical theorists argued that political practices were largely constructed by how people thought about them (and vice versa). Thus, it was thought “reflective” IR perspectives would yield not only academic progress, but possibly more peaceful, just and “emancipatory” worlds, too. Despite current pessimism, these hopes were not entirely unfulfilled, and the rise of critical IR is a core focus of my PhD.

Contextualising IR’s Growth

Third Debate self-images were particularly popular in Britain, which had long incubated a small IR field connected to Law and History, but now saw an elaborate disciplinary architecture emerge. Two important journals were founded in the 1970s, namely Millennium at the London School of Economics (LSE) and the British Journal of International Studies (later Review of International Studies), while the British Journal of Politics and International Relations dates from 1999. All were premised on, or provided outlets for, the development of an intellectually expansive IR. British scholars such as Steve Smith and Margot Light were also prolific among a growing cast of “stock-takers”, publishing influential state-of-the-discipline essays and textbooks surveying IR’s newfound variety. In tandem, university departments and courses were remade.

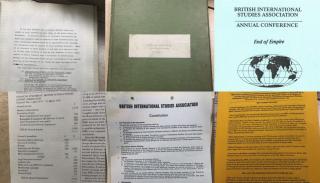

Established in 1975, the British International Studies Association (BISA), whose papers are housed in the LSE Library, served as a hub for much of this activity. In addition to publishing the Review and a book series, the archive reveals how members, operating through BISA committees, conferences, and working groups, helped grow IR in Britain and beyond. Grandees such as Susan Strange, Barry Buzan, and A.J.R. Groom connected Anglo-American scholars to a growing world of IR knowledge, forging and institutionalising links with emerging communities in Europe and Japan especially, as well as pushing an increasingly prominent International Studies Association (ISA) to become more inclusive.

Yet there were also limits to growth. Even at the time, many observed that much of Hoffmann’s account remained valid, with mainstream scholars steadfastly defending IR’s “core” from outposts in elite US institutions. Furthermore, even as the discipline grew in the UK and elsewhere, IR could still be described as US-centric given that many pioneers of new approaches trained or worked in North America, whose journals and well-endowed universities retained global prestige. Meanwhile, the category of “dissidents” was circumscribed, with post/de-colonial and Global South voices being marginalised – a situation that has only recently begun to shift.

Other complaints have been raised against celebratory growth narratives, notably regarding (mis)uses of Kuhn. In my research, I explore two less noted complications. First, not only did American neorealism not fade as was hoped – as seen during the Ukraine crisis – but interest in the broader “realist tradition”, and the nature of realism, increased. Whether it was critics uncovering genealogies of “classical” realism against which modern incarnations could be unfavourably compared, or neorealists responding with updates (defensive, offensive, neo-classical etc.), realism’s decline was accompanied by competition over the “true” realism. This can be termed the battle to #KeepRealismReal, to use the hashtag from Paul Poast’s informative twitter threads.

Second, IR’s flourishing coincided with the years of neoliberal globalisation, the defeat of Global South revolt, the rise of the “New Right”, and US unipolar supremacy. These developments were notoriously crowned by Francis Fukuyama – himself an interested reader of IR debates at the time – as “the end of history”. This raises the question of how IR’s internal “opening up” related to a closing down of political possibility in the external world, embodied in the triumph of the West and Western liberalism. If so, what does it mean for IR today, particularly considering the crisis of liberal order and ongoing re-examinations of IR’s imperial/Eurocentric past?

Disciplinary History

Despite these qualifications, IR certainly transformed in the late twentieth century, with the start of the twenty-first maintaining the trajectory. It is now self-consciously studied and researched through as many lenses, in as many places, and by as many people as ever before. By way of comparison, there seems no figure or paradigm in IR comparable to the shadow John Rawls has cast over Anglo-American political theory since the 1970s. While Rawls supposedly revived political philosophy from mid-century decline, in IR there are concerns about “the end of theory”, as scholars divide into camps finessing evermore complex approaches to narrower questions.

Today, a large sociological literature – with origins in the late twentieth century – documents and encourages IR’s international growth. This includes the Teaching, Research, and International Policy (TRIP) surveys and the “Global IR” movement. Curiously, however, historians of IR have yet to recount the story of these changes. This perhaps reflects the roots of the “disciplinary history” subfield, which lay in the very same late-century debates about IR’s identity – albeit in a reaction against the evolutionary Great Debates story of the 1980s.

Focusing on early-to-mid-twentieth century United States (and sometimes Britain), from the 1990s scholars such as Brian Schmidt began applying historical methods to IR’s past. “Piecing together long-forgotten debates, dusting off long-unread volumes, and tendering new perspectives on old questions,” they showed how Great Debates mythology distorted the early institutionalisation of IR, and caricatured the important ideas of classical thinkers. The implication was that evolutionary narratives were exaggerated, since they ignored connections between IR’s early and present condition. Disciplinary historians particularly highlighted the continuing power of realism, though more recently have uncovered the imperial, racialised, and gendered legacies of IR’s origins.

Yet while the Great Debates were not accurate descriptions, they did reveal something disciplinary histories often downplay. Focused on uncovering auguries of the future in IR’s deep past, disciplinary histories risk figuring IR as beholden to discourses of distant origin. By contrast, the Great Debates story highlighted the possibility of change and renewal, reflecting the late-century moment in which it was established. To understand IR today, this moment – in which disciplinary history itself was born – requires its own recovery and contextualisation. Disciplinary historians do offer useful methodological tools here, and some have partially addressed the late twentieth century, but more work is now needed to balance the focus on “origins” with the study of change over time.